Economists have long held the view that discrimination in hiring is best controlled by markets that are competitive. The rationale is that competition in the product markets will make employers cost-conscious, and that competition in the labor market will focus employers on job applicants’ workplace productivity.

Employers may harbor some biased views of job seekers based on race, sex, age or other external features. However, such employers will be punished in the competitive product market if bias leads them to turn away productive workers. The punishment will take the form of lost of sales and revenues to their competitors who don’t discriminate. The resulting lower profits ultimately leads inability to compete and closure of the affected firms.

This automatic disciplinary process is thwarted if regulatory interventions create excess labor supply conditions. A minimum wage or a wage determined by collective bargaining are both attempts to administratively elevate the wage above its competitive level. The result of the higher wages will be increased unemployment and greater latitude to discriminate. The resulting excess labor supply allows employers to express their bias without economic cost. Bias against a given sex or race of worker does not have to be strong to, nonetheless, create significant disparities in employment.

This is particularly important to current policy. The Biden administration has pledged to increase the number and power of unionized labor. In addition to making American industrial products less competitive on world markets, this amplifies the power of public sector unions. Teachers’ unions, for example, use the teachers’ union dues payments to underwrite campaigns for left-leaning politicians and teachers. This, in turn, sustains the public school monopoly and the poor quality of K12 education that results. Mr. Biden has pledged to eliminate charter schools (which generally are non-union) because they outperform the more costly unionized public schools.

As noted earlier, a side effect of unionized wage-setting is that it makes discrimination in hiring more likely. Indeed, as Nobel-Laureate economist Gunnar Myrdal observed in his 1944 book, An American Dilemma, “…the fact that the American Federation of Labor as such is officially against racial discrimination does not mean much. The Federation has never done anything to check racial discrimination exercised by its member organizations.” The same could be said about teachers’ union opposition today to public funding of private schools for black students.

In 2019, Lincoln Quillian et al. published a detailed study of job discrimination across 8 countries using actual data on the outcome of job applications by white versus non-white applicants. This affords an opportunity to illustrate the impact of unionization on discrimination because the influence of unions on wages varies significantly across countries. The study used data from 200,000 job applications to determine whether the minority applicants experienced a lower rate of callback than their otherwise-similar white jobseekers. In low discrimination countries the minority applicants experienced callback rates were about 25 percent lower than white applicants. In the high discrimination countries, the minority applicants were treated 4 times more negatively than white applicants.

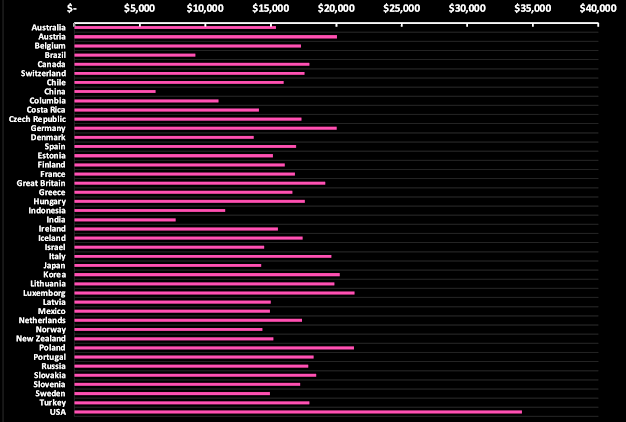

For each country, a discrimination score was developed as a ratio of the number of applications that must be submitted by a minority applicant to expect an equal chance of a callback as a white applicant. Figure 1 illustrates a general tendency for counties with high levels of collective bargaining to have high levels of discrimination. In contrast, as the regression line in Figure 1 illustrates, countries with lower levels of collective bargaining tended to lower levels of discrimination as well.

The simple correlation across all countries in the sample is approximately +50%, which implies a moderate positive relationship between unionization and discrimination. An oft-used alternative measure of the degree of discrimination is the unemployment rate of the minority applicant to that of a white applicant. That correlation from that approach is less persuasive. The observed correlation is typically +20%, which is much weaker than the correlation displayed here.

Figure 1: Correlation between Collective Bargaining and Discrimination

The authors had expected that the mainly socialist-leaning European countries would perform better than countries like the US, with less elaborate labor regulations. In fact, as argued earlier, such intrusions create exactly the conditions in which job discrimination is expected to thrive. Indeed, Sweden and France, display the highest rates of discrimination, and also had the highest shares of wages determined by collective bargaining.Norway, the Netherlands, and Belgium received low discrimination scores, despite the large share of wages that are subject to collective bargaining. However, the small labor markets limited the number of applications that the researchers could study. The US cohort f applicants had data from 73,000 applications whereas the number of applications available for study were only 3,500 to 6,000 for these three smaller countries. In fact, the researchers considered the scores statistically insignificant. They are plotted in Figure 1 for completeness sake and also because, within the group, higher rates of collective bargaining seem to be associated with relatively higher discrimination rate scores. This observation, however, does not survive testing for statistical robustness, however.

The German markets, with only about 50 percent of wages subject to collective bargaining fit the hypotheses some what better and, infant their discrimination score is not testable different from the US score. The low (12 percent) collective bargaining percentage of the US is consistent with our competitive and relatively unregulated labor and product markets. It is ironic that politicians who otherwise would describe themselves as progressive would embrace policies that will likely encourage greater unemployment and discrimination of minority workers.

Sources:

Quillian, Lincoln, Anthony Heath, Devah Pager, Arn- finn H. Midtbøen, Fenella Fleischmann, and Ole Hexel. 2019. “Do Some Countries Discriminate More than Others? Evidence from 97 Field Experiments of Racial Discrimination in Hiring.” Sociological Science 6: 467-496