Historically, conservative economists like myself see the private, market-oriented economic system as the best way to improve the well-being and opportunities for our fellow Americans. Adam Smith’s 1776 book, The Wealth of Nations, made the first comprehensive case for the superiority of private markets with private capital as the means of achieving the greatest welfare from the economy’s scarce resources. Consquently, Smith is sometimes called the Father of Capitalism.

Smith argued that one could confidently rely on private markets because, in following their own self interest, private producers have the strongest incentive to discover and produce what consumers want. Smith was distrustful of leaving the management of the economy to government both because of its lack of motivation and because of the inevitable loss of personal liberty. As he put it in these thoughts:

“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.”

“I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good.”

In 1950, the French-born economist Gérard Debreu proved Smith’s intuition mathematically by showing that a competitive, private markets would yield a stable economy. His proof, using topology and other advanced mathematical demonstrations, won him the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1983. (It is officially the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel.)

Socialism, in contrast, asserts some inherent advantage from giving control of the economy to government rather than the marketplace. Unnlike capitalism, socialism has offered no scientific justification for either its stability or efficiency. It relies on the false premise that a bureaucratic system can better determine people’s needs than the people themselves.

It is also the case that most true socialist experiments have failed, including the UK, Israel, India and the Soviet Union. Most justifications of its modern use are ad hoc and political in nature. This quote from the socialist US politician Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, illustrates the vagueness of the claims articulated in its favor:

“To me, what socialism means is to guarantee a basic level of dignity. It's asserting the value of saying that the America we want and the America that we are proud of is one in which all children can access a dignified education.”

Nonetheless, many western countries, including the US, have parts of their economies that are essentially “socialized”. K12 education in the US is one of our most prominent examples. The balance between use of a private market economy (capitalism) or a government command-and-control economy (socialism) is reflected in the extent of taxation. As the name implies, a free market economy is one that is guided by “the invisible hand”. A more socialized economy relies on the explicit guidance of the very visible hand of government. Thus, notions of a democracy that advances individual freedom conflict with use of the socialist path.

Alexis de Tocqueville, the 19th century French historian and political writer, stated the conflict this way:

“Democracy and socialism have nothing in common but one word, equality… while democracy seeks equality in liberty, socialism seeks equality in restraint and servitude.”

In my view, the virtues of liberty and efficiency that attend market capitalism more than compensate for any disparities that may occur in market outcomes. Despite the imbalances among individuals that may arise, everyone can enjoy a higher standard of living than would otherwise be the case. In extreme cases of income disparity, re-distributional assistance can be provided by tax policy and voluntary aid. Conversely, a case can be made that regulating equality of outcomes retards the standard of living for everyone though adverse effects on work behavior.

The current emphasis in political circles on the supposed inequality of the US household income distribution are intentionally—or ignorantly—distorting the data. Specifically, critics of the current distribution of income in the US ignore the fact that households with high shares of income also pay disproportionately-high shares of income taxes. When after-tax income is studied, it reveals that the US actually has the most progressive distribution of net income after taxes of any OECD country, as we have shown in a previous blog. However, these facts are ignored by progressive critics of the US economy. They would rather continue to assert that the most successful households are “failing to pay their fair share” of taxes.

At the same time, critics fail to note that socializing a marketplace tends to create inefficiency and disparity. Indeed, the most inefficient and dysfunctional sectors of the US economy are those that are dominated by government-provided or controlled services. This includes the K12 public school system, the highway system, the public health system, and public housing.

All of these are either inefficient government monopolies, or heavily regulated to the point of restricting and distorting supply. This calls into question to logic of diverting funds from the private sector to the government sector to improve the equity or efficiency of a marketplace.

Taxes and Social Democracy

Nevertheless, many European economies embrace socialism to varying degrees. Many characterize themselves as social democracies—i.e., a democracy with some socialized aspects. Social democracies do not own or directly control all of the industries or sectors of production, as did the Soviet Union. Many businesses are free to operate with relative freedom and under private ownership. Thus, they are not true socialist economies.

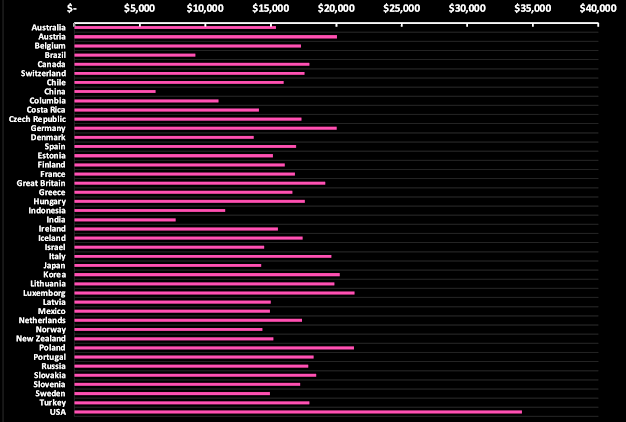

However, inevitably, the greater the share of GDP taken by government through taxation, the smaller is the influence of private sector decision forces. The decision process in government enterprises lacks the self-disciplining forces that makes the private market so efficient and productive. Social democracies are thus readily distinguished by their high tax burdens and the attendant loss of private market efficient. The purpose of this blog post is to illustrate the different degrees to which countries have avoided or embraced the insertion of government authority over the private markets.

Of course, it is also possible to use regulation to interfere with private market forces without levying taxes or owning enterprises. Many social democrat countries select to do so, however, in addition to employing high levels of taxation. This is because there are limits to taxation, and regulating behavior is a more occult way to exert control over the private sector.

Regulation can be very insidious because it is not necessarily subject to the same scrutiny and oversight as is a change in tax policy. In Sweden and France, for example, nearly 100 percent of wages are set by collective agreement of unions and the government rather than set privately in the marketplace.

As a first approximation, however, it is interesting to compare the total share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) that is diverted from the private sector in the US versus Sweden versus the average OECD country. Figure 1 displays the GDP shares by type of tax for each of these three examples.