The US economic and political system is under attack by left-wing politicians and academics who find fault both with our free-market economy and the Constitution that guides our public policies and legal systems. Now in place, the Biden administration appears be adopting policies that are antithetical to these key aspects of our society. The left, it seems, believes we would be better off if we relied instead on socialist approaches whereby government exerts direct and granular control over more aspects of our lives.

Some of the discussion focuses on publicly provided services, such as education and public health care. As an economist, I agree that both sectors are underperforming in the US, but would argue that the problems arise from too much public sector control—not too little. It is certainly not because we spend too little in these areas. In 2018, for example, the U.S. spent 16.9 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) on health care, nearly twice as much as the average OECD country. Similarly, In 2017, we spent $12,800 per student on public education. This is the second-highest of any country in the world.

Switching to a model with even more government involvement and spending is thus hard to justify. Rather, the inept government intervention in both markets should be addressed by greater privatization and competition. For example, our public school system is a monopoly run for and by its unionized management and labor. It should be replaced by one where parents and their students are in practical and financial control, and have choices about where and what the students learn. During the Covid-19 pandemic, parents got front row, video access to the biased and corrupt state of education in US K12 classrooms.

Similarly, our health system would benefit from removal of the government policies that constrain the supply of health care workers, raise the cost of drug development, make the cost of care opaque, and couple insurance access to employment. Again, all of these changes would bring more, not less, competition and pricing discipline to health care. The vaunted, government run health care monopolies are not the solution. Direct regulation of doctor salaries, for example, may bring down cost superficially, but notoriously impose costs in the form of queues for service and rationing of access.

In most other parts of the economy, such competitive supply and pricing prevails. In so doing, market reigns, the free market elevates our high standard of living. We can easily demonstrate that our greater use of private markets affords the average American a much higher standard of living than other developed countries. Measuring the “standard of living” can be done at various levels of granularity, such as measuring the number of rooms in one’s house, the number of automobiles owned, televisions owned, food eaten, etc. But the simpler and more agnostic approach is to measure the annual dollars that are able to be spent by households on consumption. Doing so on a per capita basis helps adjust the measure for differences in family size.

There are some challenges in measuring the standard of living this way across multiple countries. For example, countries use different currencies whose variable values have to be considered. In addition, the supply conditions of specific goods and services vary greatly across countries. A commodity that is very costly to purchase in one country may be cheap to obtain in another. The goal is to normalize these variable factors and achieve so-called Purchasing Power Parity (PPP). The basic idea of PPP is to use the prices of specific goods to compare the absolute purchasing power of the individual countries' currencies

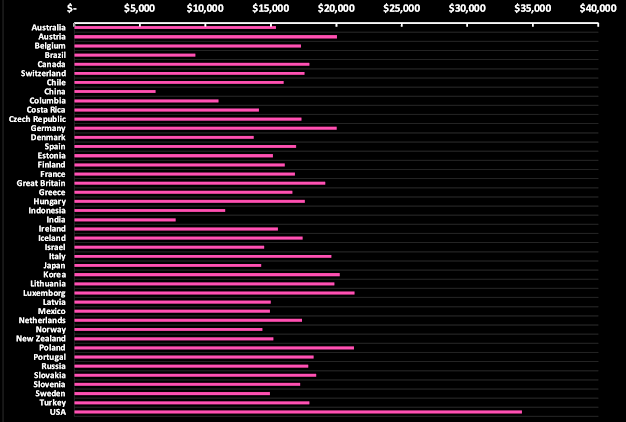

The purpose of this blog is to do just such measurements for the various countries so the comparisons can be made with that of other developed economies. The Biden administration’s policies seem to be modeled on increasing socialization of the economy. Thus, I have drawn the sample from OECD member economies, some of which are modeled on this philosophy. We can then see whether consumers perform better or worse under a socialized regime versus a private market regime such as ours.

The resulting measures of consumer spending use the International Dollar as the unit of value after adjustment of their original currency. Since the International Dollar measure is available benchmarked to 2011, I obtain the nominal measures (of consumer spending, exchange rates and PPP) in that year for each country. The US dollar is the currency to which exchange rates and PPP adjustments are benchmarked and thus the US CE needs no adjustment. The adjusted results for others are presented graphically in Figure 1.